Edition 2009

BRIAN GRIFFIN

Retrospective, The Water People, L’Équipe, Team, The People Who Built The Channel Tunnel Rail Link

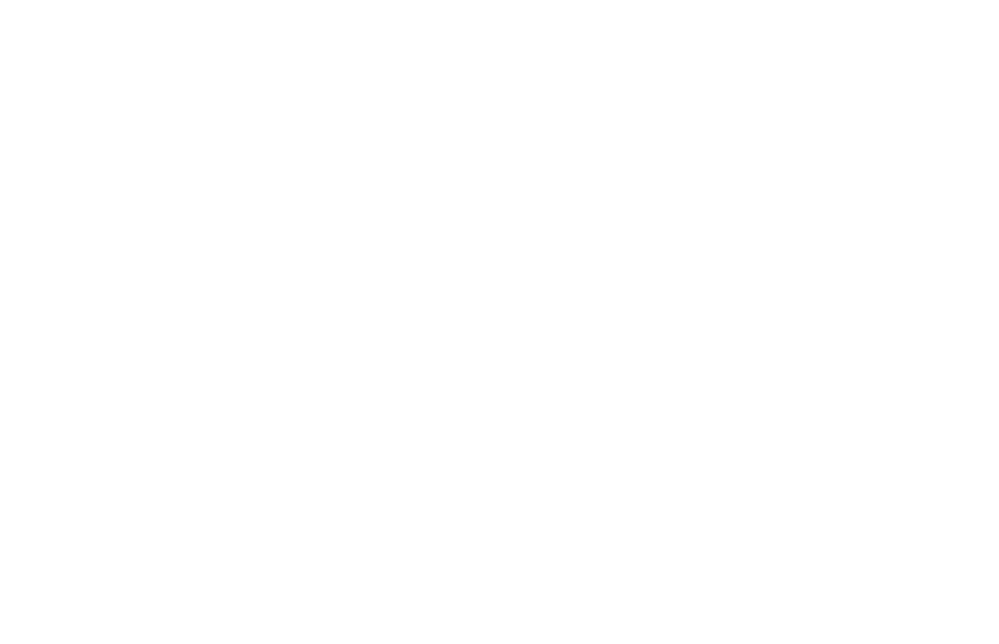

Retrospective

My life as a photographer began in 1966, working in a factory making conveyors, in the Black Country, an area close to Birmingham. The factory foreman proposed that I join the local camera club. Why he introduced the subject of photography I have no idea. To be truthful, although I joined the local camera club and bought my first camera, I wasn’t overcome with interest. It was not until 1969 when I was working in an office in Birmingham as a nuclear pipe work engineering estimator that things radically changed for my photography and me. My girlfriend at the time suddenly left me, leaving me bereft and devastated. Life was now empty and I hated every aspect of it, so in a panic to escape I desperately applied to photography colleges for a place as a full-time student. Photography was the only escape that I felt I had at my disposal. I have no idea why in my desperation I felt so confident, for the images I had taken up to then were dreadful and displayed little talent, together with my only having a half-interest in the subject.

Manchester College of Art and Design was the only one to offer me a place. Photography in the late sixties was not a fashionable subject to study in England. Essentially the teaching and tutors were awful, all ex-Royal Air Force, but I had a great time living away from home for the first time. Whatever I learnt was in the college library, and I left at the end of three years knowing photographically very little. But I had grown into a young man who could look after himself. I graduated from college in 1972. The next eight weeks were spent working in a steelworks to earn some cash to pursue my ambition to become a professional photographer in London.

Any illusion of making it was severely tested and almost shattered until at the point of failure and desperation after three or four months walking the streets of London I met Roland Schenk, the art director of the magazine Management Today, who to my amazement offered me a job on the spot. It’s interesting that I learnt later that both Roland and I abide by the rule that at the point of absolute failure arrives success. He taught me to be a good photographer by psychologically terrorising and beating me into shape, until I could be relied upon to produce something interesting from what was essentially boring subject-matter. Here I was back photographing people in business and offices, an environment that I had left in desperation three years earlier. This was the last area of photography that interested me, but it was my only chance. Also in the early seventies it was the least fashionable area of photography. Roland, who was Swiss and a fine artist, helped me find my way and to source inspirations. After two years of trying to find my creative way I found it through a combination of German Expressionism, film noir, music, the writer Franz Kafka and Soviet Social Realism — probably because these elements visually and sonically reminded me of my childhood growing up in the Black Country in the 1950s. I began to start to place my business subjects into my own piece of theatre. In the theatres of my imagination it was exciting to see all these directors and accountants as actors in my plays, with their offices my theatrical backdrops.

In 1976, I took (in my opinion) my first great image, of people going to work in the City of London, its title Rush Hour London Bridge, inspired by the film Metropolis by Fritz Lang, and I breathed a sigh of relief knowing that from now on I could make it as a photographer.

Brian Griffin, December 2008.

The Water People

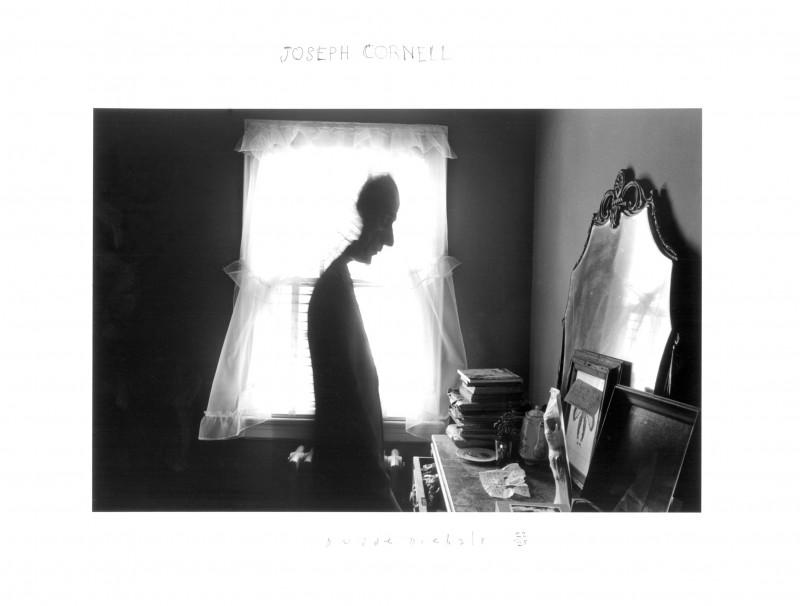

To people familiar with Brian Griffin’s portraiture, his exhibition The Water People may come as something of a surprise. Portraits make up less than half of the images in both, and only a handful of them tap into his expertly noirish style. The other portraits are distorted abstractions taken through water, and many of the other images are starkly beautiful landscape shots of Iceland. Griffin is married to an Icelander, Brynja Sverrisdottir, but he says that the main inspiration for shooting the island came from a commission from Reykjavik Energy, a geothermal energy company. ‘I like getting a commission and then working out how to do it’, he says. The original commission was simply to ‘represent water’ and Griffin was free to interpret it exactly as he saw fit. His unique solution to the project might have come as nearly as much of a surprise though — a photographic search for The Water People. ‘I designed a machine a long time ago which flowed water down a piece of glass in front of portrait sitters’, he explains. ‘When I got this commission I remembered it, and asked Reykjavik Energy to build another one for me. I set up a studio in their offices and photographed people using it — everyone from Bjork’s mother to people working in the office. I really liked the fish eyes it created. Then I started to think about where these water people would live and the Jules Verne novel Journey to the Centre of the Earth’, he continues. ‘The waterfalls and water are like the underground caverns in the book, and they are where the water people are to be found’.

Following this theme, images of the ‘pilots’ who took him to see the water people feature at the start of the exhibition, the Reykjavik Energy headquarters reinterpreted as a mysterious meeting place of the pilots. Eccentric as this approach is, it’s also backed up with stunning photography, which Reykjavik Energy has been free to use in its corporate reports. Griffin, who started out shooting corporate portraits for Management Today, is a past master at getting corporate backing for his esoteric projects.

Diane Smyth, deputy editor of the British Journal of Photography.

Team, The People Who Built The Channel Tunnel Rail Link

How do you capture the monumental scale of Britain’s largest ever construction project? The completion of High Speed 1, the building of a new corridor for the high-speed railway ending at the cathedrallike terminus of St. Pancras International, has been well documented along the way. But Greg Horton, the art director hired by London & Continental Railways (LCR) as a creative consultant, felt such a mammoth undertaking deserved more powerful imagery to convey its magnitude.

What’s more, he knew a photographer with a bit of history at shooting epic projects; one who could bring a sense of heroism to the thousands of workers involved in HS1’s nine-year construction. From his seminal 1980s series, Work, on the building of Broadgate in the City of London, to his recent commission from Reykjavik Energy, The Water People, to shoot Iceland’s remarkable geothermal infrastructure — both published as books—Brian Griffin has become world renowned for his unconventional approach to corporate portraiture, employing complex lighting set-ups and introducing a sometimes surreal twist to his compositions. LCR took a leap of faith, but when they saw Griffin’s imposing photographs of construction workers tasked with building ‘the Stratford Box’, an underground box containing the platforms for Stratford International station, they shared Horton’s vision. Griffin captured the workers at St. Pancras in a makeshift car-park studio, visualising them as courageous figures, lending them a valiant status through his trademark directional lighting, classic use of black and white and formal posing, reminiscent of Russian Constructivist imagery. No doubt buoyed by an award-winning feature in the Sunday Times Magazine, LCR gave the green light to extend the project under Horton’s direction, leading to what Griffin believes is the most substantial corporate book of photographs since the Great Exhibition of 1851.

While the workers are portrayed as heroes, the managers — the thinkers controlling this massive undertaking — are caught in more contemplative mood, shot in cinematic compositions while making decisions among the city of portacabins around the St. Pancras construction site. In group images, the managerial teams are given a more painterly treatment, visualised as seventeenth- century patrons and photographed as if posing for a Frans Hals portrait, frozen in celestial gazes, while US-based project engineers are pictured in mysterious, slightly surreal little narratives — puzzles to be solved. It’s a typically maverick approach to a corporate commission from Griffin, whose committed artistry and complex approach to his subject have resulted in images that are truly worthy of such an impressive engineering triumph.

Simon Bainbridge, Editor, British Journal of Photography.

My life as a photographer began in 1966, working in a factory making conveyors, in the Black Country, an area close to Birmingham. The factory foreman proposed that I join the local camera club. Why he introduced the subject of photography I have no idea. To be truthful, although I joined the local camera club and bought my first camera, I wasn’t overcome with interest. It was not until 1969 when I was working in an office in Birmingham as a nuclear pipe work engineering estimator that things radically changed for my photography and me. My girlfriend at the time suddenly left me, leaving me bereft and devastated. Life was now empty and I hated every aspect of it, so in a panic to escape I desperately applied to photography colleges for a place as a full-time student. Photography was the only escape that I felt I had at my disposal. I have no idea why in my desperation I felt so confident, for the images I had taken up to then were dreadful and displayed little talent, together with my only having a half-interest in the subject.

Manchester College of Art and Design was the only one to offer me a place. Photography in the late sixties was not a fashionable subject to study in England. Essentially the teaching and tutors were awful, all ex-Royal Air Force, but I had a great time living away from home for the first time. Whatever I learnt was in the college library, and I left at the end of three years knowing photographically very little. But I had grown into a young man who could look after himself. I graduated from college in 1972. The next eight weeks were spent working in a steelworks to earn some cash to pursue my ambition to become a professional photographer in London.

Any illusion of making it was severely tested and almost shattered until at the point of failure and desperation after three or four months walking the streets of London I met Roland Schenk, the art director of the magazine Management Today, who to my amazement offered me a job on the spot. It’s interesting that I learnt later that both Roland and I abide by the rule that at the point of absolute failure arrives success. He taught me to be a good photographer by psychologically terrorising and beating me into shape, until I could be relied upon to produce something interesting from what was essentially boring subject-matter. Here I was back photographing people in business and offices, an environment that I had left in desperation three years earlier. This was the last area of photography that interested me, but it was my only chance. Also in the early seventies it was the least fashionable area of photography. Roland, who was Swiss and a fine artist, helped me find my way and to source inspirations. After two years of trying to find my creative way I found it through a combination of German Expressionism, film noir, music, the writer Franz Kafka and Soviet Social Realism — probably because these elements visually and sonically reminded me of my childhood growing up in the Black Country in the 1950s. I began to start to place my business subjects into my own piece of theatre. In the theatres of my imagination it was exciting to see all these directors and accountants as actors in my plays, with their offices my theatrical backdrops.

In 1976, I took (in my opinion) my first great image, of people going to work in the City of London, its title Rush Hour London Bridge, inspired by the film Metropolis by Fritz Lang, and I breathed a sigh of relief knowing that from now on I could make it as a photographer.

Brian Griffin, December 2008.

The Water People

To people familiar with Brian Griffin’s portraiture, his exhibition The Water People may come as something of a surprise. Portraits make up less than half of the images in both, and only a handful of them tap into his expertly noirish style. The other portraits are distorted abstractions taken through water, and many of the other images are starkly beautiful landscape shots of Iceland. Griffin is married to an Icelander, Brynja Sverrisdottir, but he says that the main inspiration for shooting the island came from a commission from Reykjavik Energy, a geothermal energy company. ‘I like getting a commission and then working out how to do it’, he says. The original commission was simply to ‘represent water’ and Griffin was free to interpret it exactly as he saw fit. His unique solution to the project might have come as nearly as much of a surprise though — a photographic search for The Water People. ‘I designed a machine a long time ago which flowed water down a piece of glass in front of portrait sitters’, he explains. ‘When I got this commission I remembered it, and asked Reykjavik Energy to build another one for me. I set up a studio in their offices and photographed people using it — everyone from Bjork’s mother to people working in the office. I really liked the fish eyes it created. Then I started to think about where these water people would live and the Jules Verne novel Journey to the Centre of the Earth’, he continues. ‘The waterfalls and water are like the underground caverns in the book, and they are where the water people are to be found’.

Following this theme, images of the ‘pilots’ who took him to see the water people feature at the start of the exhibition, the Reykjavik Energy headquarters reinterpreted as a mysterious meeting place of the pilots. Eccentric as this approach is, it’s also backed up with stunning photography, which Reykjavik Energy has been free to use in its corporate reports. Griffin, who started out shooting corporate portraits for Management Today, is a past master at getting corporate backing for his esoteric projects.

Diane Smyth, deputy editor of the British Journal of Photography.

Team, The People Who Built The Channel Tunnel Rail Link

How do you capture the monumental scale of Britain’s largest ever construction project? The completion of High Speed 1, the building of a new corridor for the high-speed railway ending at the cathedrallike terminus of St. Pancras International, has been well documented along the way. But Greg Horton, the art director hired by London & Continental Railways (LCR) as a creative consultant, felt such a mammoth undertaking deserved more powerful imagery to convey its magnitude.

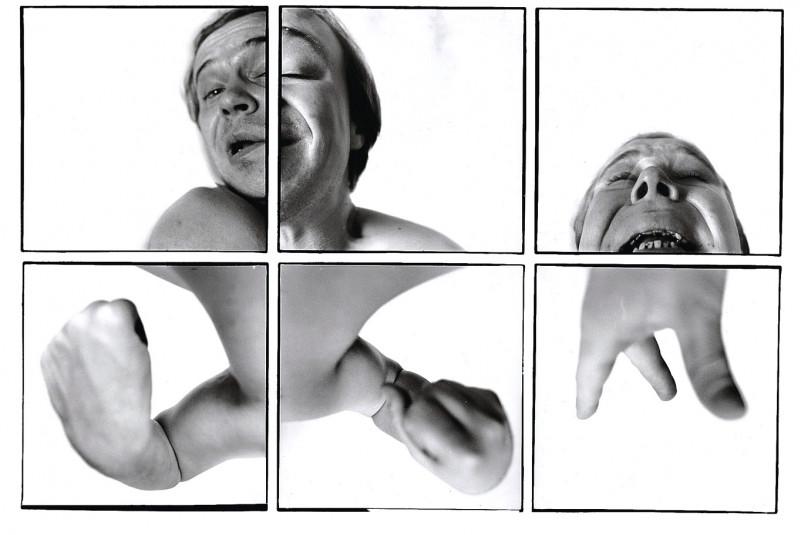

What’s more, he knew a photographer with a bit of history at shooting epic projects; one who could bring a sense of heroism to the thousands of workers involved in HS1’s nine-year construction. From his seminal 1980s series, Work, on the building of Broadgate in the City of London, to his recent commission from Reykjavik Energy, The Water People, to shoot Iceland’s remarkable geothermal infrastructure — both published as books—Brian Griffin has become world renowned for his unconventional approach to corporate portraiture, employing complex lighting set-ups and introducing a sometimes surreal twist to his compositions. LCR took a leap of faith, but when they saw Griffin’s imposing photographs of construction workers tasked with building ‘the Stratford Box’, an underground box containing the platforms for Stratford International station, they shared Horton’s vision. Griffin captured the workers at St. Pancras in a makeshift car-park studio, visualising them as courageous figures, lending them a valiant status through his trademark directional lighting, classic use of black and white and formal posing, reminiscent of Russian Constructivist imagery. No doubt buoyed by an award-winning feature in the Sunday Times Magazine, LCR gave the green light to extend the project under Horton’s direction, leading to what Griffin believes is the most substantial corporate book of photographs since the Great Exhibition of 1851.

While the workers are portrayed as heroes, the managers — the thinkers controlling this massive undertaking — are caught in more contemplative mood, shot in cinematic compositions while making decisions among the city of portacabins around the St. Pancras construction site. In group images, the managerial teams are given a more painterly treatment, visualised as seventeenth- century patrons and photographed as if posing for a Frans Hals portrait, frozen in celestial gazes, while US-based project engineers are pictured in mysterious, slightly surreal little narratives — puzzles to be solved. It’s a typically maverick approach to a corporate commission from Griffin, whose committed artistry and complex approach to his subject have resulted in images that are truly worthy of such an impressive engineering triumph.

Simon Bainbridge, Editor, British Journal of Photography.

www.briangriffin.co.uk

Brian Griffin is représented by Ardenandanstruther and England & Co Galleries.

Réalisation : Olivier Koechlin.

Executive producer: Le Tambour qui parle.

Pictures printed by Lighthouse Darkroom, London.

Framing by Circad.

Exhibition projected at the Atelier de la Maintenance, Parc des Ateliers.

A first retrospective was presented in Arles in 1987.